So you want to be a rule of law defender?

A speech by Eleanor Sharpston, March 17th, Brussels

Introduction by the Our Rule of Law Team

The past 6 months of organising the Our Rule of Law Academy has been full of unbelievable moments. One of such moments was when we received a Twitter DM from former Advocate General at the ECJ, Eleanor Sharpston saying “please would you send me your info pack, Many Thanks Eleanor Sharpston”. A few days later, we had a public video-lecture to mark the opening of applications with Princeton Professor Kim Lane Scheppele - a powerhouse of a woman and a personal inspiration to all four of us. And out of the blue, former Advocate General at the ECJ, Eleanor Sharpston joined the Zoom Call. That was one of those moments where online meetings shine - you can gasp and laugh in excitement without anyone noticing.

Eleanor Sharpston served as Advocate General at the Court of Justice of the EU from 2006 to 2020. She is famous for her opinions as Advocate General amongst EU law circles - for example, her opinion in Ruiz Zambrano, the landmark case on citizenship, free movement of persons and fundamental rights, is stock material in any European Law course. Another example is her opinion on the obligations of Czech Republic, Poland and Hungary to effectively enable relocation of asylum seekers amongst Member States.

Ms Sharpston originally studied economics, languages and law at University of Cambridge. She was a barrister in private practice for a number of years - she could well be called a celebrity barrister in the UK. Sharpston is also an educator who has taught EU and comparative law at University College London and at the University of Cambridge, where she is still a fellow at King’s College.

Ms Sharpston was terminated before the expiry of her term as Advocate General at the General Court as a consequence of Brexit. She has challenged the termination in front of the CJEU, going all the way, but she lost the case. Many commentators have pointed to the determination as a sign of non-respect for rule of law within the EU institutions themselves - and she used all the legal venues available to challenge it.

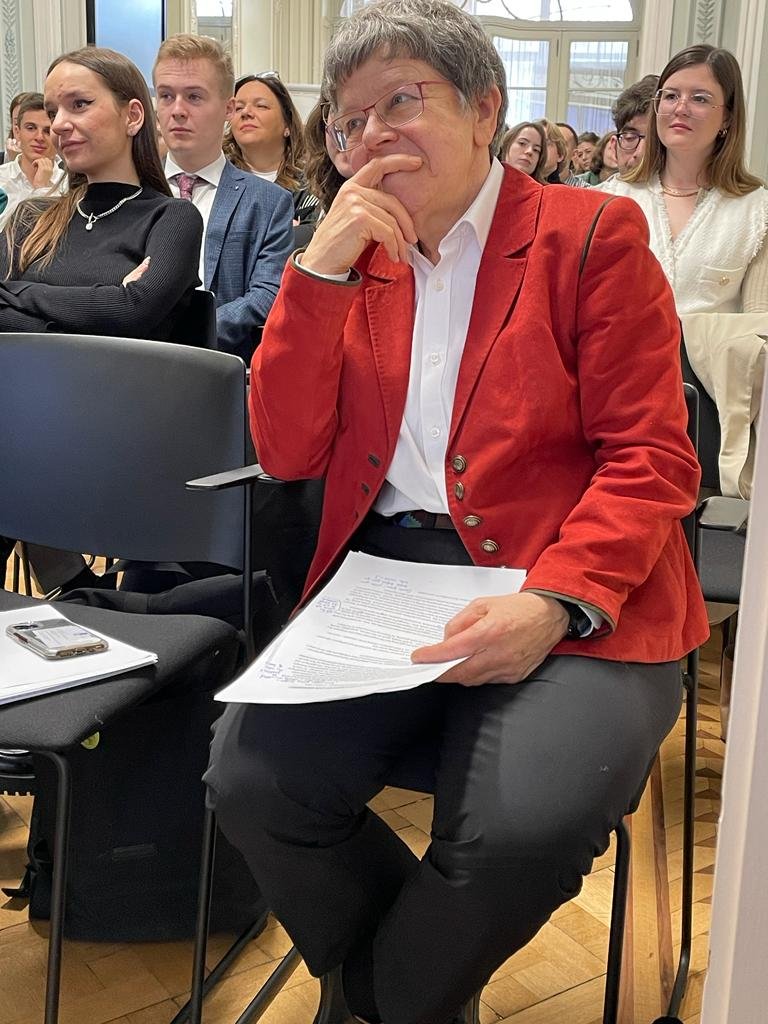

In short, Ms Sharpston is a tower of extraordinary talent and experience. It has been an inspiration engaging with you both online and in person in Brussels, and we are honoured that you have taken the trip from Luxembourg to be here for the Academy, Eleanor. Thank you.

Closing speech for the Our Rule of Law Academy by Eleanor Sharpston

I want to take you back to – well, a date in early prehistory (to be accurate, in 1981). There I am – a keen, eager young lawyer: wildly idealistic, committed to justice and the rule of law – and it’s my first day going into court as a newly qualified barrister acting for a real client. I had a defence brief to prepare a ‘plea in mitigation’ for the sentencing hearing for a character who (let’s put this politely) was not having his first encounter with the criminal justice system. Everyone (including my solicitor and the client himself) was pretty sure that he was going to ‘go inside’ this time, the only question being how long a prison sentence he would get. My job, doing the plea in mitigation, was essentially damage limitation. As I was in the middle of looking up everything I could think of checking (I vastly over-prepared that hearing!), my supervisor (my ‘pupil master’), Cyril Newman, popped his head round the door to see how I was getting on and to offer well-meaning reassurance. I asked him if he had any top tips for me doing my first case for real. Without hesitation he replied, ‘Yes … make sure that you have really polished your shoes before you go into court’

I remember looking at him in utter disbelief. Cyril was a delightful, old-fashioned, English gentleman. Was this an example of the celebrated English sense of humour? Was it designed to get me to relax a bit? Did he conceivably mean it for real as a piece of advice?

Let me answer those questions in order.

First question: maybe. I never found out; and since I couldn’t be sure that he was joking, yes, I did polish my shoes that evening as well as looking up the law; and then I polished them again just before I went into court.

Second question: as pre-first hearing advice, I have to tell you it did not produce a feeling of zen-like relaxation. Rather the reverse. I became even more worried than I was already. Apparently I don’t only have to know all the relevant law: it seems that I also have to have beautifully polished shoes.

Third question: actually, when I got to court, the first thing that the magistrates’ clerk did was to look sharply, not at my face, but yes, at my shoes. Having satisfied himself that they were polished and gleaming, he looked up from my shoes to me with a pleasant smile.

The magistrates’ clerk was very helpful to me after that throughout that memorable day. His helpfulness really mattered because the one thing I hadn't prepared for – happened. My client didn’t turn up for court. When the case was called on for hearing: no client! And the magistrates, who were really not amused, promptly issued a ‘bench warrant’ for his arrest. That of course meant that he would be in a whole lot more trouble: not just the original charge that he was being sentenced for, but a whole stack of other problems.

Thanks to the unobtrusive kind hints from the magistrates’ clerk, I did manage to salvage the situation. I got the police not to execute the arrest warrant (so the additional problems to which that would have given rise quietly went away). I got the case relisted for hearing at the end of the day. And – I think to everyone’s surprise – I did actually keep my client out of prison.

My first encounter with the justice system as a barrister, and a number of valuable lessons. The one I want to flag up for you today is this: issuing the bench warrant for my client’s arrest was simply wrong. The magistrates were annoyed he wasn’t there. (How rude. How disrespectful. We are important people, we are the court – he should be here on time.) They weren’t prepared to consider that they should give him a bit more leeway. Why? Because there might be a perfectly innocent explanation for why he wasn’t there precisely on time for the hearing. (By the way, there was indeed an innocent, even a banal, explanation. He had simply caught the wrong train. He was the kind of guy who catches the wrong train in life.) The magistrates took a hasty decision, influenced by their annoyance. That decision was an incorrect use of their powers. There was – in short – a mini rule-of-law issue in this tiny, routine hearing in a minor criminal court. I had to find a way of (politely!) unscrambling the mess and getting my client treated justly. Thanks to those useful hints from the magistrates’ clerk, who had liked my nicely polished shoes, that’s what happened.

You are all eager, motivated, rule of law defenders. So – here are five ideas, five principles for you to apply.

First principle. Do not accept the status quo without asking questions first.

We are all taught to regard our own legal system as the natural way of doing things. Obviously it adds up, it makes sense. It is the embodiment of justice-meets-law. (English lawyers are particularly prone to making this assumption, because we just know in our bones that the English legal system, based on the sacred common law, is naturally superior to any other legal system.) More generally, however: we all have an instinctive respect for our own legal system. Of course it makes sense and of course (naturally, ladies and gentleman, naturally) it is impeccably fair

Whoa. Wait a minute please. Just ask yourself the question: does my legal system really always guarantee fairness and the rule of law? Let me give you a couple of dubious examples from the English legal system: one from recent, the other from more ancient, times.

The recent example comes from the middle of all the Brexit shenanigans. As you maybe know, the UK doesn’t have a written constitution, but there are numerous ‘constitutional conventions’ which are meant to do the job instead because, naturally, they will be respected. One of those conventions is that, save for specified ‘recesses’ (breaks), Parliament is meant to be in session to deal with Parliamentary business. And yet, in September 2019 we suddenly saw a 6-week prorogation of Parliament. (Please remember, Brexit was meant to be about giving control back to Parliament.) Why? Well, Parliament had started asking tedious questions about what exactly was being negotiated and whether it was a sensible form of Brexit. So, how much better for the executive not to have a Parliament meeting for six weeks during that crucial period. Then it could present Parliament with a fait accompli and rush the deal through before the (then) deadline for leaving the European Union on 31 October 2019. It took a trip to the Supreme Court financed by a very public-spirited (and wealthy) ordinary citizen, Gina Miller, to get that prorogation of Parliament declared unlawful.

A much older example, one of the most notorious miscarriages of justice under the English legal system, was the case of the ‘Birmingham Six’.

For years already, in what were euphemistically known as “the Troubles”, there had been sectarian bombings and shootings in Northern Ireland. Atrocities were committed by armed groups on both sides. In 1974 the IRA extended their campaign into mainland Britain. On 21 November 1974, 21 people were killed and almost 200 injured when bombs exploded in two public houses in Birmingham. This was the deadliest attack on English soil during the 30 years of the Troubles. Six Irish immigrants (who became known later as ‘the Birmingham Six’) were arrested, charged with the bombings, convicted and sentenced (in 1975) to life imprisonment.

In 1976 a first application for leave to appeal was dismissed. In 1988 a first full appeal was dismissed and the convictions were upheld as ‘safe and satisfactory’. In 1991, on a second full appeal with additional fresh evidence, their convictions were finally quashed. The basis for quashing those convictions was police mishandling of the evidence and indications that the defendants’ convictions had been coerced. Just to give you a flavour of what had been happening: I was told by the defendants’ solicitor that a key piece of evidence for the prosecution at the original trial had been tests carried out on the defendants’ hands which were said to reveal the presence of nitro-glycerine, which was one of the components used in making the Birmingham pub bombs. The only problem is, the same test would also show a positive result if you had recently washed your hands with commonly available soap. Think about that for a minute. The Birmingham Six spent fifteen years inside prison because the English legal system failed to recognise and take proper account of that possibility of a false positive. Everyone (except a few rule of law campaigners) was sure that the English criminal justice system was infallible. An atrocity had been committed and these Irish defendants must be guilty. The system is good, and we never convict the wrong person. Except when we do.

So, don’t accept the status quo without asking (lots of) questions first.

Second principle. Do not expect opportunity to knock at a convenient moment (because it never does), just take the opportunity when it comes – and remember that you can also go out there and look for that opportunity.

From the perspective of some 43 years in the profession, allow me to share with you an unpalatable truth. Opportunity never, by any chance, arises at the right moment.

Opportunity doesn’t come along when you’re just sitting there peacefully and you’ve got plenty of time, at 10 o’clock on a Wednesday morning when there’s nothing much else in your diary for the rest of the week. No, no. Opportunity will always turn up at a moment when you are harassed and overworked. It will turn up at 10pm on a Sunday evening (I know, I know). It will turn up late on a Friday afternoon before a holiday weekend. It will turn up when you cannot imagine how on earth you are going to fit this additional demand into your day along with everything else that is already happening.

And the news is: you have got to fit it in. The news is: if this is something that needs doing, somehow you have to make the space to do it. And if you really care about being a rule of law defender and an opportunity hasn’t knocked at your door for a while – well, you know, you can go out and look for it. There is an awful lot happening. There is an awful lot of pro bono work that needs doing. There are many tribunals which make decisions that matter to people, but where those concerned cannot get legal aid to pay for representation. There is an awful lot that can be done, and you can do the work applying the principle of cross-financing. What I mean by that is that you have ordinary work that you do that pays the rent and pays for your food; and then you cross-subsidize. You buy your own time, in order to invest that time in pro bono work that needs to be done. If I think back over my practising time at the Bar, the cases that come immediately to mind, the ones that I found most fulfilling and that really gave me most satisfaction, the ones that I still have a warm glow about – all of them are cases that I did pro bono. That’s an interesting reflection.

Third principle. Actively consider whether this small, insignificant, unimportant case that you are currently doing is maybe the case that is going to break new ground if pleaded in a new way.

Of course, it is very easy to see the rule of law point after the event. Once a point has been picked up and has been pleaded, of course it’s obvious. We all understand that under the surface, just waiting to be brought out, there was a really interesting human rights point. There was a point that could be run under the ECHR. There was a breach of fundamental rights under the constitution. There was a breach of due process. Yes, we can all spot the point with hindsight, once a bright lawyer has got up and said “hang on, wait a minute, I am not sure that was okay”. Be that bright lawyer! Always ask yourself that question.

Fourth principle. Every case matters.

Every case is about an individual. To you, it may be yet another case in a long and possibly boring series: “Oh yes (yawn), this is the 15th bylaw application I am doing this week.” To your client, it is THE case (definite article). It's the only case that matters. It’s his case, it’s her case; it’s his or her entire future. And for that reason, it deserves your best, every single time.

It’s a bit like being an actor. You can’t say to the audience tonight, ‘I'm sorry but I’m feeling rather “off”, I’ve got a bit of a stomach upset. I’ll do my best with playing Hamlet but you’ll have to cut me a bit of slack if I don’t really do “To be or not to be …” quite as well as you might expect me to.’ No, no, no. Your audience came to the show tonight, and you have to give them the best performance you can

As we say in Ireland, ‘it’s the same difference’ with being a lawyer. If you are representing a client, the client doesn’t care how good you were last week; and the client doesn’t care how good you may be next week. The client needs you to be on top of your game today, because today is when you are representing him.

Finally, the fifth and most important principle. Having your heart in the right place, dear friends, isn’t actually enough. You have to be technically better than your opponents, than the lawyers earning the fat fee notes who are acting on behalf of the big corporations or acting on behalf of the State.

I owe this last thought – the very best advice that I was given as a young lawyer – to my wonderful mentor at King’s College, Cambridge: Ken Polack. Ken’s heart was absolutely in the right place for every good cause you can think of. But by training Ken was a company lawyer (and a very good company lawyer at that). Ken was meticulous to the point of obsession about getting everything – every last detail – nailed down correctly. If there was a gap in your logic, a gap just about big enough for a mouse to squeeze through, Ken would find it. He would point it out to you, and he would explain how and why it made all the difference. Because that little mouse-sized gap would have allowed the court to go the opposite way to the way that you were arguing for.

Sometimes a point may sound a bit technical. Perhaps it is some fiddly little procedural or evidential rule that you learnt at law school but never seriously thought would matter in real life. And yet the day may come when that little procedural or evidential rule may be the key to getting a result that is accordance with the rule of law.

Dear friends, let me echo Daniel Sarmiento’s words to you yesterday: the rule of law should be in the DNA of every lawyer working in a liberal democracy. Remember, democracy is not a given. Nor are the values it incorporates. Democracy is something that we need to fight for every day. As lawyers we are privileged to be able to do that through striving to uphold the rule of law, wherever we practice, whatever precisely we are doing. And so: enjoy your professional journey; enjoy the law and do it with commitment, do it with creativity, and (yes) sometimes do it with passion.